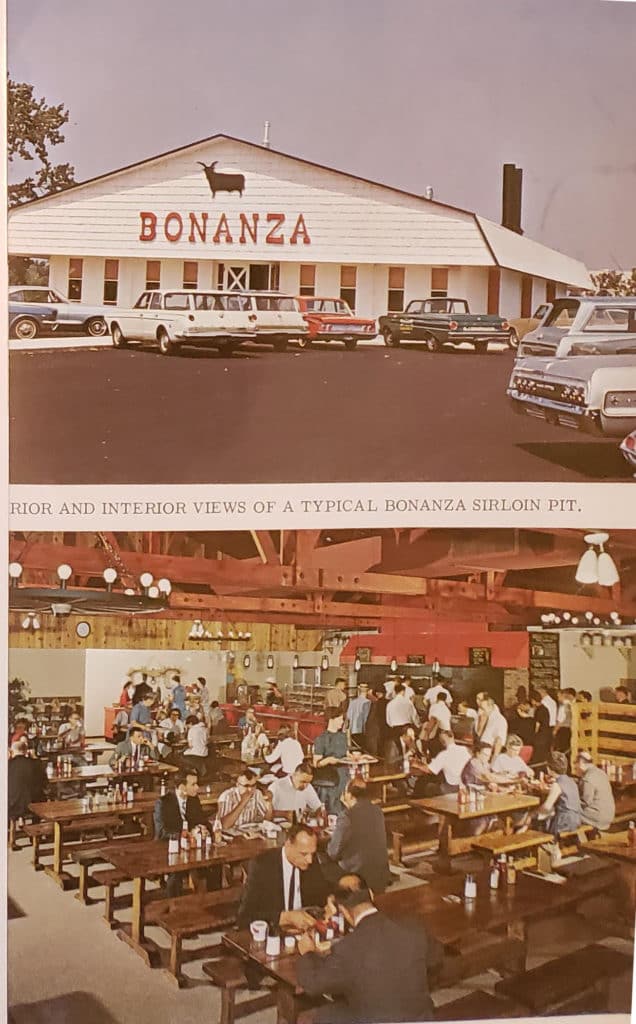

My mom used to be a chef in the suburbs of Chicago cooking at two restaurants my family owned - an Italian steak house called Bonanza and a fried chicken shack called Phone-a-Feast. My mom was the chef at the first Bonanza and it did so well it grew into a new life as a steak house chain across the United States that sourced its meat from the Angus farm my family owned. They believed in all-alfalfa-fed cows way before it was the thing, because “It just seemed right,” as my grandpa put it. He drew all the advertisements for both businesses—I learned to draw because of him. It’s the first restaurant my family tells stories about on holidays.

Grandpa (4th from the right)

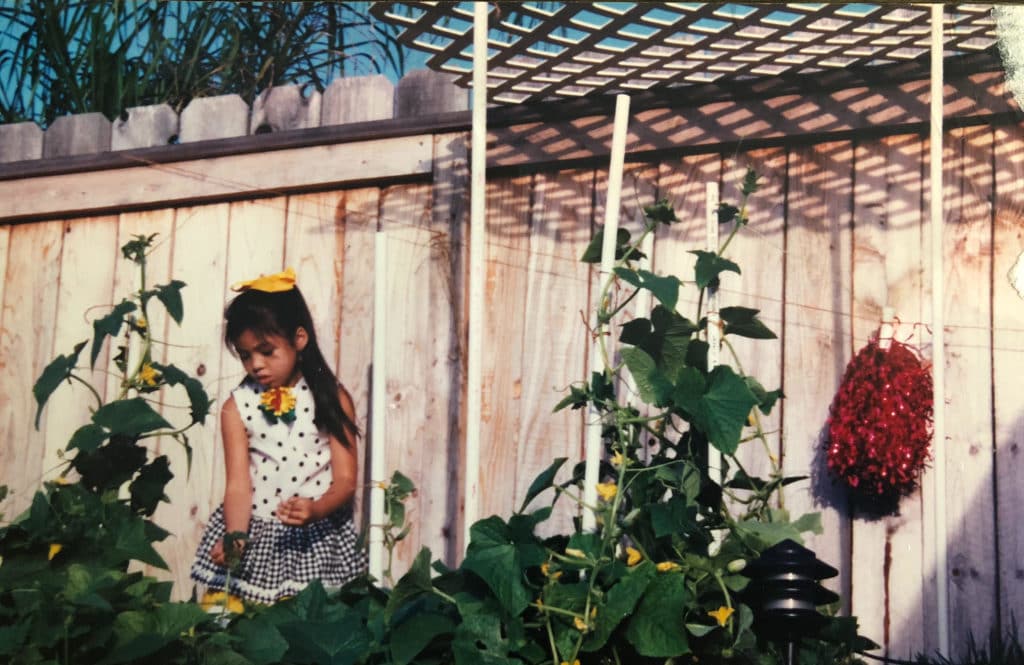

As the restaurants grew, my mom grew disenchanted with the restaurant business in general and moved to the west coast for a fresh start, while continuing to cook for our family and explore things she didn’t get to in a restaurant format. There are photos of me tucked into a baby backpack, looking over her shoulder in fascination at all the fast cooking action. I started making my own bread and pasta at age eight; I needed to a booster stool to even reach counter height.

Lexie cooking with Mom.

The values my mom instilled as I learned to cook have greatly shaped my own methodologies as an architect. I learned from her to persist in creative problem-solving. I learned that you need many iterations, and that there are many ways to accomplish a spectacular end result, because there is not a finite singular way to solve any problem. I learned to be open minded and to listen to your materials—they will tell you what they need. You can’t manhandle dough into submission—you have to walk away and let it rest, it will consider your efforts. And sometimes, it’s just too humid to make caramel, because too much moisture in the air prevents sugar and fat from binding together. Listen to your ingredients, understand your context and restraints, they will inform you how to move forward.

Pizza and dough made by Lexie

Cooking and architecture are similar in a lot of ways. Both start with simple, unpolished ingredients that you combine to make a new, polished whole, greater than the sum of its parts. Think about how you make bread by bringing together ingredients from very different sources: flour, which is processed from wheat; salt, a naturally occurring mineral and yeast, a bacteria found everywhere. And yet bread is an infinitely flexible recipe—it can be a simple yet honed skill like a crusty ciabatta bread or an intricate process with many ingredients and layers like Greek Easter bread. Architecture is very much the same. You have distinctive building materials —steel, glass, wood, concrete— each have a life span of their own that, when they come together, can create something completely different.

With both food and architecture, the creativity of the combining process gives cultural context and meaning. It makes the separate materials, whether flour or concrete, culturally specific. The process of connecting uncommon ingredients for the same utilitarian purpose but with a different creative flare gives people common ground, a lens to understand each other across generations or across different cultures. You can see how cultures have changed over time by looking at how their cuisine has changed, how their cuisine has been influenced by other cultures, scientific developments and prevailing ideas of the time - the same can be said about architecture. Both are intimate responses to the essential in a specific context.

In each case, the end products are highly interactive. The compositions you create, whether a plated dish or a building, are personal experiences for the user AND the creator. They provide a connection for all those separate materials, made through laborious care. To me, that’s beautiful and authentic.

At their best, both architecture and culinary arts appeal to many of the senses at the same time. The most memorable meals I’ve had are an experience, its not just about the food, it’s the space, the smell and the interaction. Of the top three meals I’ve had [in no particular order, Michael Mina (SF), Wolves Den (Los Angeles), and Pierre Gagnaire (Paris), the food was an extraordinary element of a much more interesting whole. Part of it is the interaction of who you’re with and the way the food descends upon the table for each course. You are immersed in the smell and the character of the moment. All of these experiences were especially accentuated by how carefully crafted each ceramic is for that specific dish and experience. In one case, cedar smoke is carefully concealed in dishware and only escapes once you move your spoon to waft at you and wet your palate before you taste its contents. In another memorable case, the ceramics stack and pour their flavorful contents from one layer to the next flavoring each layer as you make your way down the stack and appear to defy gravity until you have the courage to approach this delicious ‘Alice in Wonderland-esque’ set up only to realize each plate is magnetized to the next. Each create a moment that far exceeds taste, and captures your fascination. All of this to fulfill the essential and ascend from it.

I think this is very synonymous to what architects aim to provide. Architects always think of their buildings as a multi-sensory experience. All are based on fulfilling an essential need and exceeding that necessity to capture a moment, and make connections to a time, place and context apparent a user that would not have been obvious otherwise. I think, that is the kind of thing we’re all going for architecturally, whether in residential, educational or commercial.